Members’ Award Exhibition: Imisinga (Currents)

Date

Artists

The show will feature a range of selected works from KZNSA Members.

For more Info, contact us on: gallery@kznsagallery.co.za

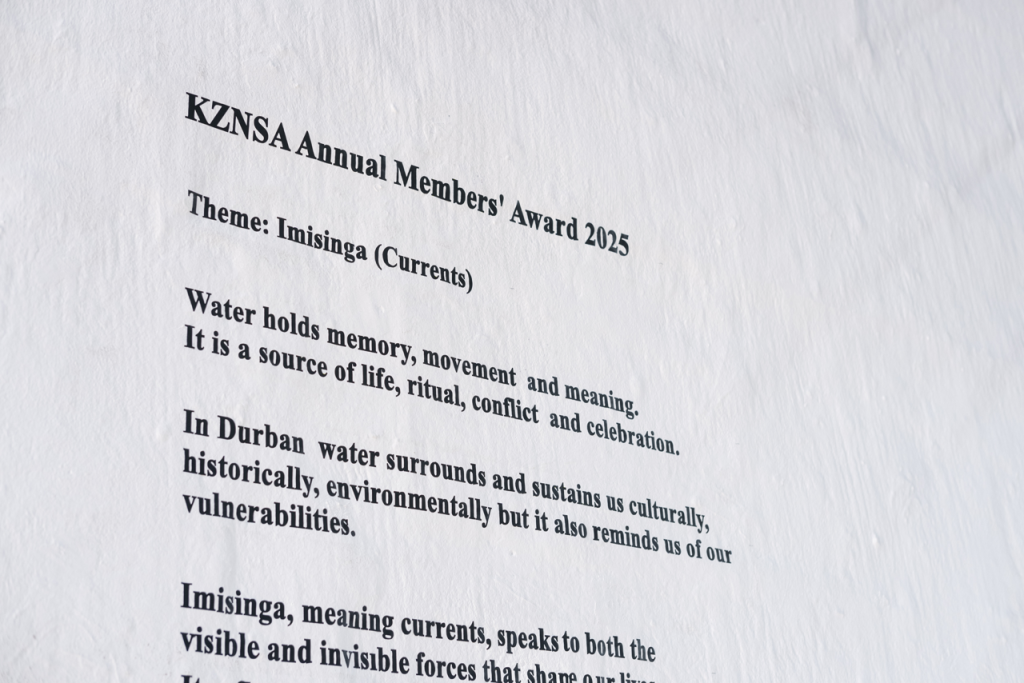

Water holds memory, movement, and meaning. It is a source of life, ritual, conflict, and celebration. In Durban, water surrounds and sustains us—culturally, historically, environmentally—but it also reminds us of our vulnerabilities.

Imisinga, meaning currents, speaks to both the visible and invisible forces that shape our lives. It reflects the pull of history, the surge of change, and the fluidity of identity.

This year’s Members’ Award theme invited artists to engage with water in its many forms and contradictions. As we navigate rising seas, floods, pollution, and strained infrastructure, we also witness water’s resilience—its power to renew, connect, and transform.

From literal depictions of ocean tides and rainstorms, to symbolic interpretations of flow, survival, resistance, and adaptation, this exhibition gathered diverse responses to the currents that run through our city, our communities, and ourselves.

27 works were selected by the KZNSA Exhibition Sub-committee through an anonymous adjudication process. This year’s independent judges; Nindya Bucktowar, Jess Bothma and Xola Mlandu went on to select the top three artworks.

First place went to Thobani Khanyile for his soft pastel drawing titled Woeful Studies. Ann-Marie Tully came in second place with her mixed-media piece, The Mercantile Infanta [Wabi Sabi]. Third place went to Gary McIver for his oil painting, Threshold. The Merit Award went to Grace Kotze for her acrylic painting, The Animals Within.

The Prize money and the Joan Emanuel floating trophy are generously sponsored by the Key Foundation and the Joan Emmanuel Trust.

First place received the Joan Emmanuel floating trophy, R20 000 and a solo exhibition at the KZNSA in 2026, the second place R10 000, and third place R5 000. A Merit Award, selected by the KZNSA Exhibition Sub-committee was given to a fourth work.

Ann-Marie Tully

The Mercantile Infanta [Wabi Sabi]

2025

Intaglio tetrapack on reclaimed linen lappies, vintage handmade lace, brass dowel and chain

42 x 42cm

R 4 500,00

Indivisible

2025

68 x 48cm (framed)

R 1 200,00

Re-Entry

2024-2025

Oil on canvas

110 x 75cm

R 33 333,33

Aftermath 2

2025

4 Colour Reduction Woodcut on Fabriano Cold Pressed

64 x 53cm (framed)

R14 166.67 unframed

SUNRISE

2025

Oil on canvas

80 x 120cm

R 11 000,00

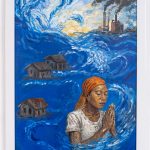

Still Can’t be Washed Away

2025

Mixed media

80 x 75cm

R 15 998,33

Clay and Rocks

2025

Terracotta

30 x 24cm

R 58 333,33

The Blue Economy

2025

Mixed media, collage, thread, fishing gut, found object [plastic bag] on 300g Fabriano

87 x 117cm (framed)

R 13 333,33

Ukuvela

2025

Water paint and black ink pen on canvas

114 x 158cm

R 30 000,00

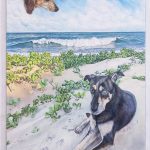

Grace Kotze

The Animals Within

2025

Acrylic on canvas

90 x 70cm R 25 000,00

Strange Currents

2025

Denim, cotton thread and embroidery hoop

Various sizes (set of 5)

R1 300 (can be sold separately)

Lets Fly Away 3

2024-2025

Oil on canvas

62.5 x 50cm

R 7 500,00

imisinga yangaphakathi

2025

Acrylic on board

42 x 60cm

R 20 833,33

Rip Tide of Influence

2025

Oil on canvas

60 x 60cm

R 3 600,00

The Fading Memory

2025

Mixed media on canvas

15 x 30cm

R 33 333,33

A Deluge

2025

Oil on canvas

76 x 60cm

R3 331.67

Currents 1, 2 and 3

end 2024

Mosaic

15 x 15cm each (set of 3)

R450 each

Currents 1, 2 and 3

end 2024

Mosaic

15 x 15cm each (set of 3)

R450 each

Currents 1, 2 and 3

end 2024

Mosaic

15 x 15cm each (set of 3)

R450 each

Glistening Still

2025

Acrylic on canvas

92 x 92cm

R 8 900,00

Alluvium

2025

Mixed media installation consisting of Eco-prints, vitreous enamels on copper, and sterling silver

42 x 53 x 15cm

R 15 000,00

Alluvium

2025

Mixed media installation consisting of Eco-prints, vitreous enamels on copper, and sterling silver

42 x 53 x 15cm

R 15 000,00

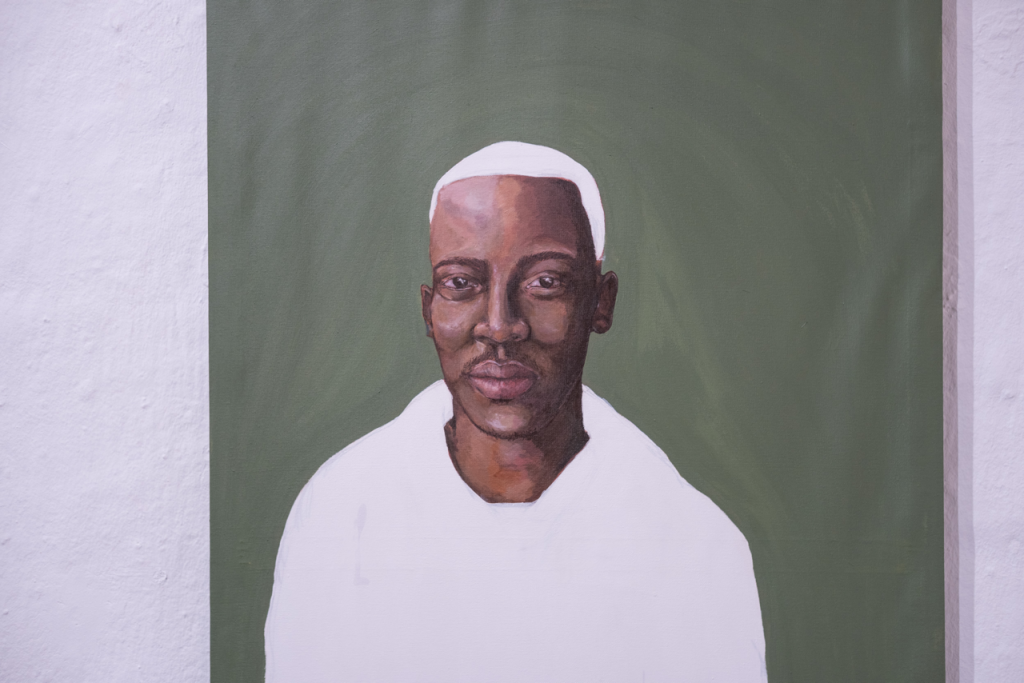

Thobani Khanyile

Woeful Studies

2025

Soft pastel

59 x 84cm

R 11 500,00

Currently with Pepsi

2025

Oil on canvas

76.5 cm x 51 cm

NFS

Contrast & Harmony

2025

Mixed media on mounted board

100 x 100cm

R 8 750,00

Gary McIver

Threshold

2025

Oil on board

39 x 44cm

R 20 000,00

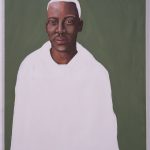

Emsamu (the sacred still life)

2025

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 90cm

R 25 000,00

Poitu Varen [I will go and come back]

2025

Assemblage, Fiber Sculpting, Printmaking

120 x 82 x 16cm

R 5 000,00

Silhouettes of Loved Ones

2025

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 117cm

R 26 000,00

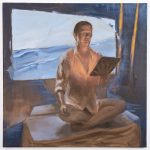

OM

2022

Acrylic on canvas

126.5 x 101cm

NFS

Submerged Currents: A Critical Reflection on Imisinga and the KZNSA Annual Members’ Award 2025

The KZNSA Annual Members’ Award 2025 exhibition, titled Imisinga (Currents), is a striking example of how contemporary South African art can harness metaphor, material, and memory to interrogate socio-political realities. Centered around water as both a literal and symbolic element, the exhibition is deeply informed by the recent environmental disasters in KwaZulu-Natal, especially the April 2022 floods. Through the works of artists such as Thobani Khanyile, Ann-Marie Tully, and Gary McIver, Imisinga becomes a site where aesthetics and political commentary interweave. This essay critically explores how Imisinga not only reflects but challenges dominant narratives of environmental degradation, state neglect, historical amnesia, and emotional survival, situating the exhibition within broader academic discourses on climate justice, postcoloniality, and curatorial practice.

Water as Metaphor and Method

Water in Imisinga is not treated as a passive background or symbolic flourish; it functions as a methodological tool for thinking through crises. Drawing on Gaston Bachelard’s Water and Dreams (1942), where water is seen as a medium of depth, fluidity, and unconscious emotion, the exhibition embraces the polysemy of water-as a source of life, carrier of memory, and instrument of destruction. Bachelard suggests that water mirrors our most intimate fears and desires; in Imisinga, water reflects collective trauma and submerged political neglect.

Furthermore, the framing of water as a current draws from Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic (1993), where the ocean becomes a space of forced movement, loss, and diasporic identity. Similarly, Imisinga understands water as both connector and separator. In a Durban context-a city bordered by the Indian Ocean and shaped by colonial port histories-the current becomes a metaphor for dislocation, migration, and erasure.

Durban as Archive and Witness

The exhibition situates Durban not merely as a locale but as a living, breathing archive. The 2022 floods, which killed over 430 people and displaced thousands, are a central subtext. As documented by the South African Human Rights Commission and echoed by local media like Mail & Guardian, the disaster revealed long-standing failures in urban planning, drainage systems, and emergency response. Imisinga engages with what Achille Mbembe (2001) calls “the materiality of failure” in postcolonial governance. Durban’s decaying infrastructure, built on colonial legacies and apartheid-era spatial planning, becomes a key interpretive lens.

This local archive intersects with broader global climate justice debates. Scholars such as Rob Nixon (2011) in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor argue that environmental catastrophes disproportionately affect the poor and marginalized, often through long-term neglect rather than sudden disasters. Imisinga makes visible this slow violence through its focus on vulnerability, grief, and structural abandonment.

Curatorial Politics: Refusing Resolution

The curatorial strength of Imisinga lies in its refusal of didacticism. Instead of offering clear narratives or solutions, the exhibition embraces ambiguity and contradiction. This aligns with Terry Smith’s (2012) notion of the “contemporary” as a condition of simultaneity and multiplicity. The exhibition resists linearity; it drifts, floods, recedes, and re-emerges.

The decision to curate around water invites a form of curating as method, rather than theme. As art historian Irit Rogoff (2006) argues, critical curating should not simply display artworks but produce knowledge and disorientation. Imisinga does exactly that-forcing the viewer to engage affectively and ethically, rather than intellectually alone. Its power lies in what it does not explain.

Artworks as Aesthetic Interventions

Among the standout works, Thobani Khanyile’s Woeful Studies presents a haunting image of a cow submerged in murky floodwaters, with a bright rubber duck floating nearby. The visual irony and tension mirror Judith Butler’s (2004) concept of “precarious life,” where certain bodies are rendered more grievable than others. The cow’s expression, both innocent and alarmed, implicates the viewer in the act of witnessing. The rubber duck, a symbol of childhood innocence, becomes a surreal counterpoint to the devastation-a trace of the absurdity of state failure.

Ann-Marie Tully’s The Mercantile Infanta [Wabi Sabi] offers a different modality of critique. Through her use of tetrapack prints on reclaimed linen, Tully invokes the materiality of waste and consumption. The childlike figure in the work, adorned with lace and Indonesian tattoo motifs, recalls the entanglements of colonial trade, environmental ruin, and spiritual hybridity. Her work resonates with Jane Bennett’s (2010) Vibrant Matter, which advocates for an ethics of care towards the material world. Tully’s stitched, fragile surfaces become embodiments of planetary fragility.

Gary McIver’s Threshold is perhaps the most introspective of the featured works. A face submerged in water, referencing the River Styx and Gustave Doré’s illustrations of Dante, captures a moment of suspended emotion. The piece channels what Christina Sharpe (2016) calls “the weather” in In the Wake, a term she uses to describe the atmospheric conditions of Black life under racial capitalism. McIver’s image, quiet yet weighty, becomes a psychic site of mourning and witnessing.

Materiality as Message

Across the exhibition, materials are not neutral; they are ideologically and environmentally charged. The use of tetrapack, soft pastel, reclaimed linen, and drawing speaks to a politics of reuse, of working within the limitations of scarcity. This aesthetic of salvage aligns with what anthropologist Anna Tsing (2015) describes in The Mushroom at the End of the World as “the arts of living on a damaged planet.”

This is particularly poignant in a post-flood Durban, where debris and destruction are part of the visual and lived landscape. The artists do not sanitize or beautify this reality; they incorporate it, literally and symbolically, into their work.

Conclusion: Submersion and Survival

Ultimately, Imisinga is not an exhibition about water-it is water. It flows between themes, resists containment, and reflects both light and depth. Its strength lies in its ability to hold contradiction: grief and beauty, memory and forgetting, urgency and reflection.

In a time when art is often expected to provide answers or serve as development propaganda, Imisinga reclaims art’s capacity to bear witness, to evoke, to disturb, and to hold space. It reminds us, as the closing lines of the exhibition text suggest, that we are already submerged-not just in water, but in history, politics, and precarity. And like the tide, we must learn not only how to resist, but how to move with what remains.

References

- Bachelard, G. (1942). Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. Dallas Institute Publications.

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

- Butler, J. (2004). Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence.

- Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press.

- Mbembe, A. (2001). On the Postcolony. University of California Press.

- Nixon, R. (2011). Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.

- Rogoff, I. (2006). “Smuggling – An Embodied Criticality.” Art Journal, 65(1).

- Sharpe, C. (2016). In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press.

- Smith, T. (2012). What is Contemporary Art? University of Chicago Press.

- Tsing, A. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press.