Disgust, Fear and Hell

Date

Artists

Zama Mwandla

For more Info, contact us on: gallery@kznsagallery.co.za

In Disgust, Fear and Hell, Mwandla confronts the spiritual and psychological burden of living in a world that continuously violates women physically, emotionally, and symbolically. This body of work emerges as a direct, intimate response to the violence she witnesses both in South Africa and globally: a culture of harm that infiltrates the everyday, distorts identity, and corrodes the soul.

The title reflects the emotional and psychic landscape through which Mwandla moves. Disgust at the cruelty and systemic disregard for the feminine body. Fear of erasure, of violation, of becoming endlessly unseen. Hell as both a lived and inherited condition, where memory and present terror coexist.

These works are not statements of resolution but raw manifestations layered expressions of dread, anguish, and resistance. While painting remains central to her practice, Mwandla expands her visual vocabulary in this exhibition to include fabric and experimental materials. Fabric here becomes a metaphorical skin at once soft and scarring, protective and ruptured. It stands in for the body, the wound, the ghost evoking the sensory and emotional weight of trauma.

Her visual language is rooted in symbolic storytelling, personal mythology, and the logic of dreams. Throughout the exhibition, hybrid, mystical figures part spirit, part creature populate the canvases. These beings embody complex emotional states and serve as both self-portraits and collective avatars. Drawing from religious iconography, myth, and surrealist tradition, Mwandla creates liminal spaces where the sacred collides with the grotesque, and where transformation is ongoing but unresolved.

Disgust, Fear and Hell does not offer healing. Instead, it immerses the viewer in the rawness of survival. It poses urgent questions: What happens to the soul when the world becomes uninhabitable? And what can art hold when words no longer suffice? Through this work, Mwandla does not search for closure but rather exposes what healing must first endure.

Eww, Disgusting sis..

2025

Fabric and mixed media on plastic base

33 x 33

I feel…

2025

Wooden board, colourful wool, keyboard keys, foil, cement, thatch fabric and acrylic paint

60 x 26 x 40

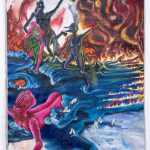

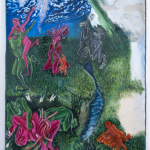

The heavens still burn, while Earth Trembles Diptych

2025

Oil, acrylic and fabric on canvas

126 x 78

The heavens still burn, while Earth Trrembles Diptych

2025

Oil, acrylic and fabric on canvas

126 x 78

On days I couldn’t go on… Diptych

2025

Oil, acrylic, fabric, pastel and embroidery on canvas

126 x 78

On days I couldn’t go on… Diptych

2025

Oil, acrylic, fabric, pastel and embroidery on canvas

126 x 78

The Rituals of the Vile

2025

Oil, fabric and embroidery on canvas

133 x 70

Let’s pour one out for the period!

2025

Fabric (cotton), embroidery, foil keboard keys, wooden baord, glass bottlesand oil paintings

200 X 40 X 90

Exhibition review: Zama Cebsile Mwandla at the KZNSA by Mbusi Mzolo

You are going to feel. What you feel might draw you closer to the work. Or it may repulse you. In cases where you are steered in the direction of seeking a deeper understanding of the work, as it was with me, you will get to learn of the tragedies that inform the creation of the pieces before you. The work is layered with signifiers and meaning, and with these comes the unshakeable feeling of despair. The colours are radiant. And the stories are dark.

The title of the exhibition, ‘Disgust, Fear and Hell’, aptly captures the essence of this collection of multimedia pieces by the award-winning Fine Arts graduate, Zama Cebsile Mwandla. Mwandla communicates her ideas and experiences in a series of visually striking compositions. The paintings are not pretty; they possess a hallucinatory and manic tone. The text is coated in despondency and confusion. The sculptures demand attention. The technique shows undeniable signs of an artist who has gone through professional training. An artist with the requisite capacity to canalise disparate thoughts and experiences. I get the sense that the work was created to make the viewer uncomfortable and get a semblance of what women endure. There is no buffer to make one easily process the ideas presented; the pieces shout at you. It is not a “could this be what I think it is?”, it is what it is. Mwandla does an incredible job of unequivocally communicating her disgust. It is especially challenging to engage with the work when you have been conditioned to believe that some things are not meant to be shown and discussed in public.

It is what it looks like when you’re no longer certain whether life is still worth living. It is a visual representation of thoughts from a woman whose experience has been marred by entitled men. The complexity makes the work interesting beyond the shock you feel at first glance. In the paintings, each figure is carefully placed to signify the different actors in a patriarchal society — victims, perpetrators and ableists. The work explores power through women’s powerlessness.

In cases where the pinkish figures are without any recognisable facial features, the signifiers are there. They are unquestionably representative of the female body through anatomy: breasts and vaginas. There is a palatable sense of conflict in every piece. In On days I couldn’t go on…, the conflict is perhaps at its clearest. The action is happening in all spheres of existence: land, air and water. The female body cannot escape the throes of patriarchy. The torment comes from the men, represented by the black mixed-breed monsters with toucan beaks, multiple tails and spikes atop the dome. This hideous mixed creature is shown engaged in a variety of eerily abusive acts. The plight of women is never a result of a single group’s actions. Mwandla shows the co-conspirators as different types of creatures. The text that is paired with the paintings serves as a great way to gain deeper insight into what Mwandla seeks to communicate through the visual elements.

There is a plethora of possible interpretations when instability is understood as a result of patriarchy. The chaos is premised on the agents of patriarchy’s entitlement to women’s bodies. And their ceaseless desire to quell women’s agency. Instead of cowering under forced authority, Mwandla chooses to place her experience at the centre of the work. The male figures and their chaos are brought on as accessories in the story. Their presence is the source of the discomfort, but this is not about them. It is about Mwandla’s story. The story is filled with various plots that are relatable on varying levels. One might relate to the themes on a macro level, as a consumer of news and GBV stats. Some will connect with the work because they see themselves in some of the acts being displayed on the canvas, text and sculptures.

Eww, disgusting, sis…, read in an ironic tone, reads like a woman making a statement to another woman. It sounds different and carries a different meaning when it’s read as, “eww, disgusting, sies!” The colossal pad sculpture, Let’s pour one out for the period! anchors the exhibition. These pad sculptures exist in the same world where men are either applauded or ridiculed for buying sanitary pads for women they are intimate with. The reaction depends on who is watching. In ‘progressive’ circles, the applause is for acknowledging the man as an ally in the fight against patriarchy — the act registers as an act of resistance against big bad patriarchy. And in the orbit of the bigots, the man is ridiculed for engaging in “emasculating” behaviour. It’s still seen as taboo for a man to partake in the care of a woman. Access to a woman’s body is normal and acceptable when the acts are extractive. When it’s time to assist in caring for the same body that is a man’s source of pleasure, an alarmingly high number of men think it’s strange and unmanly. Mwandla manages to assemble a series of thoughts and ideas through the use of the pads. Through her colossal pad sculpture, alcohol makes its presence known through the use of bottles. It is up to the viewer to piece together the connection between all these symbols and signifiers. What is not up to the viewer is reality. And the reality is, women are not experiencing life in the same way as men. The ridge between women’s and men’s experiences is widened by the perpetuation of patriarchy-fueled behaviours and attitudes.

If you find a pad disgusting, you may be part of the problem. And you may need to unlearn some things, face your fears and be disgusted by real issues like femicide and rape instead. The people who feel connected to the protagonists in her paintings might come out of the exhibition with a feeling of being seen. There’s a somewhat automatic urge for me to insert myself in whatever art I consume. It is embarrassingly vain, but it’s a gateway to grasping bigger concepts. In this exhibition, I felt like the only place I could place myself in would be in the bad guy role. That is the only place I feel is apt, as a heterosexual man. I believe at some point in my life I have — and possibly still do — fanned the flames of the scourge by being complicit in behaviours and attitudes represented by the rats and toco toucan beak monsters. That’s the uncomfortable direction Mwandla’s work pointed me to when I spent time with it. And engaged in conversation with her on how and why the work was made. The most comfortable thing would be to only engage with the work on a theoretical level. But that’s disingenuous and regressive. To honour the level of depth and candour in the works, a disconcerting reading is required. The reality is, Mwandla is disgusted and scared. Her experience is comparable to hell.

Mbusi Mzolo is a communications practitioner with a Bachelor of Arts degree (Media & Writing and Politics) from the University of Cape Town. Mzolo participated as a writer in the KZNSA Young Artists’ Project.