Broken Land

Date

Artists

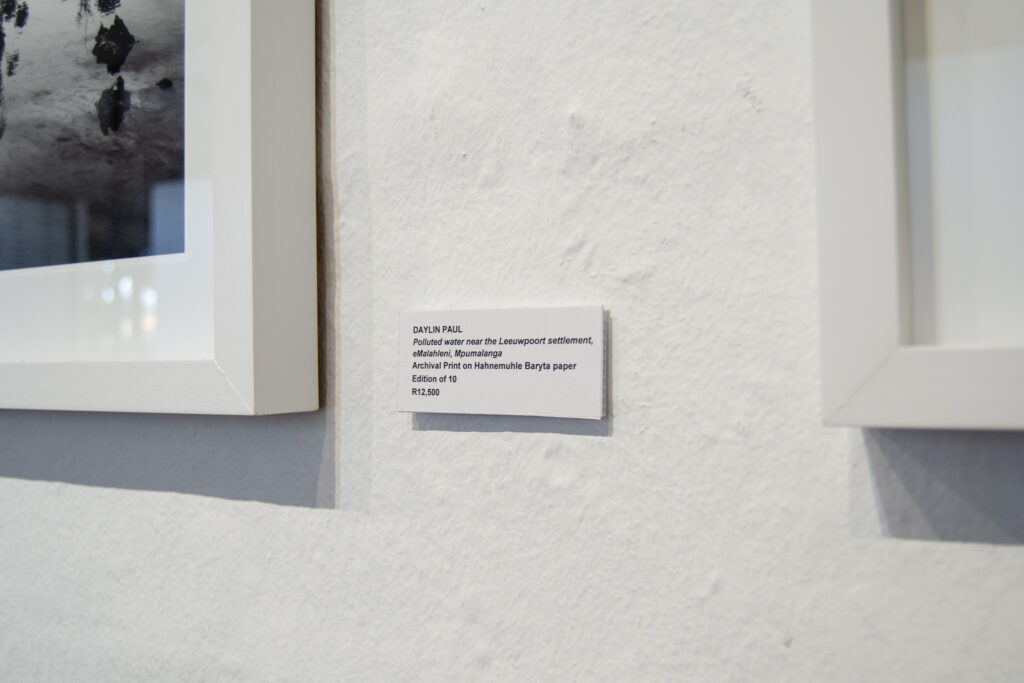

Daylin Paul

For more Info, contact us on: gallery@kznsagallery.co.za

Paul’s work explores the direct impact of fuel burning coal stations on the local economy, population, farming community and more broadly climate change. As he says, “These power stations, while providing electricity for an energy desperate South Africa, also have a devastating and lasting impact on the environment and the health of local people. Vast tracts of fertile, arable land are being ripped up, the landscape scarred with the black pits of coal mines while coalburning power stations, are one of the biggest greenhouse gas emitters in the world.” The polluting power stations not only contribute to global climate change but through toxic sulphur effluent, also to the poisoning of scarce water supplies for a range of communities who are dependent on these for their survival.

The power dynamics in the area have in recent times been drawn into the national political arena. Eskom and a conglomerate of mines owned by the Gupta family are embroiled in corruption and nepotism scandals that have affected the very highest echalons of the South African government and all levels of the economy.

The aim of Paul’s project is as he says is, “to look at both the macro issues like pollution, poverty and climate change while also personalizing the experience of the local people who are on the front lines of this crisis. This provide us with a glimpse of what the future could be like for the country and indeed the SADC region.”

After spending two years documenting on the ground, Paul says, “I can testify that the scale of destruction in Mpumalanga is wholescale. From the highways and major roads, it is difficult to get a sense of how vast the torn-up landscape is because it is often hidden behind tailings, piled close to the side of the road. It’s easy to get mesmerized by the sheer size of the mines, machines and power stations that fuel South Africa’s addiction to coal. It’s easy to forget that this affects human beings whose stories are even more beautiful and tragic than the landscape that mirrors their lives.”

While the impact on communities he found devastating, he was touched by how individual’s in various communites were willing to share their stories with him. He recounts, “I spent countless hours driving around Mpumalanga, stopping where I saw something or someone and starting a conversation. I’m still amazed at how open and sincere almost all the people I met along this journey were. How willing to share their lives and their feelings with a total stranger. The amount of trust they placed in me is a tremendous act of faith. Sebastião Salgado in conversation with John Berger once said that ‘the camera is a microphone’. My sincere hope is that I have amplified the voices of those who have shared their stories with me and not my own.”

His attempt to document the full scale of the problem humbled him by its enormity. As he observed, “The situation continues to grow on a daily basis both in Mpumalanga and across the globe as we sleepwalk ever closer toward climate catastrophe. The reporting around climate change is often cold, statistical and its symptoms are seemingly remote. But it’s true price is human and personal and its consequences are looming ominously, even now, in the present.”

This exhibition is simultaneously a documentation of the cost of extracting and burning coal, an indictment against any notion of “clean coal” and a testimony to the reality of those living close to coal mines. The project he concludes, “is also a portent into the terrifying future we face as a planet as climate change and the cumulative effect of decades of pollution adds up and demands a reckoning. It is an invaluable interrogation from the frontline of the battle to save the earth and, perhaps, our own humanity.”