AFTER 20 YEARS, 20 ARTISTS

Date

Artists

Andrew Nair

Andy Mason

Angela Buckland

Doung anwar jahangeer/dala

Bakhuli Emmanuel Many

Grace Kotze

Vulindlela Nyoni

Jeremy Wafer

Karen Bradtke

Mbongeni Buthelezi

Nanda Soobben

Pascale Chandler

Paulo Menezes

Peter McKenzie

Robert Domijan

Sifiso Ka-Mkame

Themba Shibase

Umcebo Design

Vaughn Sadie

Revolution Room

Wesley van Eeden

Woza Moya Crafters

For more Info, contact us on: gallery@kznsagallery.co.za

Critically engaged, socially relevant contemporary art making is at the core of this innovative programme. The ‘after 20 years’ exhibition is the first in the KZNSA’s 2014/15 Social Art line up.

The ‘after 20 years’ exhibition operates within the context of the anniversary of 20 years of Constitutional Democracy in South Africa. The exhibition is a large scale group showing across all the KZNSA precinct spaces, namely the Main, Mezzanine, Park Contemporary Galleries and the Durban Centre for Photography studio.

The project is curated by Independent Arts and Culture Activator Bren Brophy, in partnership with a KZNSA working group consisting of KZNSA committee office bearers, staff and associates.

The project coincides with a national election day (7th May 2014) that will see South Africans use, or not, their constitutional right to cast their ballot for local and national governance that will determine the political landscape for the next five years. Says exhibition Curator, Brophy, “The KZNSA is mindful of its own history and its commitment to a representative democratic organisational structure as outlined in its constitution. As such the KZNSA has a unique role to play in the South African Arts and Culture sector and operates with a rationale that is distinct from many of its more ‘commercial’ counterparts”.

The KZNSA does not subscribe to any party political intention and it is this independence that forms the overarching context and rationale for the development of the above project within our particular socio-historical milieu. The notion of ‘time’ and ‘place’ as well as ‘evolution’ are significant indicators that will drive the curatorial logic that we trust will inform the creative content of the ‘after 20 years’ initiative.

Arts and Culture practitioners together with the plethora of expressions that they represent have played a pivotal role over the decades. The cultural boycott, ‘struggle’ or ‘resistance’ art have become synonymous with pre 1994 modalities. Typical to these expressions was a critical approach to government and or derision across the ‘left/right’ political spectrum.

The ‘after 20 years’ project aims to reassess these methodologies with the objective of presenting contemporary art making paradigms that offer a more layered, inquisitive and investigative approach to artistic content and its relevance to the here and now.

The exhibition will host a robust educational programme for high school and tertiary learners. Developed by the ‘Art Team’ and ‘osmosis Liza’ this group of passionate art educators have developed a programme that involves what we believe to be a first for KZN Galleries, the use of QR (quick reach) codes for artworks that maximises the power of on-line and interactive components. Learners use their smart phones to engage with the artworks. The ‘Art Team’ notes that, “studies have shown that this use of communication technologies have a better chance of producing long-term learning and encouraging critical thinking than the traditional ‘outing on the school bus’.

Says Brophy, “following an extensive selection process the 20 participating artists offer a surprising array of works in all mediums that are at times reminiscent of the frustration, despair and even anger that so typified ‘resistance art’ in the eighties. This is however not just a walk down a dark memory lane, the artists have stepped up to offer a fresh voice on longstanding social and political issues and challenges. There is also, as one would suspect, a fair dose of satire. Perhaps the exhibition asks more questions than it answers, I think that is what makes these artworks so thought provoking”.

The 20 participating artists are:

Andrew Nair

Nair’s works for this exhibition is drawn from his first solo exhibition, ‘withdrawings’ (KZNSA Gallery, 2011). The chiaroscuro or ‘light and dark’ characterised by bold contrast gives the images a jewel like quality reminiscent of the 17th and 18th Century masters. Indeed Nair refers to a plethora of influences, the surrealist Georges De Cherico; Van Gogh; the Romanticist Géricault; Bruegel, and Raphael. In many instances the composition and content of each piece reflects the construction particular to specific works by these masters.

‘withdrawings’ is a highly considered series that whilst referring to the techniques and concerns of the past is in no way derivative. Nair achieves this by his consistent attention to the personal and the peculiarities of place. Many of the works depict familiar Durban cityscapes. Nair, perhaps subversively raises questions as to the nature and intent of our own ‘African Renaissance’.

Nair’s work is layered with such social commentary, whilst at the same time giving voice to intensely personal conundrums. ‘The faint light is not the light of hope, but the light that is fading’.

Like De Chirico who is best known for the paintings he produced during his metaphysical period, memorable for the haunted, brooding moods evoked by their images, Nair’s drawings combine complex psychological insights with stinging social expositions that offers a less than rosy picture of modernity. – Bren Brophy, ‘withdrawings’ exhibition Curator.

Andy Mason

The artwork consists of 15 original cartoon drawings in black acrylic ink, each on an A3 sheet of 300gsm cartridge paper, stitched together with red embroidery thread to create a “cartoon quilt” on the subject of gender and violence in South Africa today.

The drawings all relate to the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act of 2007, which repealed gender-specific common law sexual crimes such as rape and indecent assault and replaced them with gender-neutral statutory crimes, expanded the definition of rape, and introduced a range of new sexual offences.

The drawings are part of a set of illustrations commissioned by human rights law professor David McQuoid-Mason for an updated edition of “Street Law”, an illustrated practical law text for students, paralegals and concerned citizens, first published in 1987. I designed that book and provided many of the original illustrations. It was the first popular text to anticipate the reformulation of South African law preparatory to the introduction of democracy and has been used by successive generations of South African law students and paralegals since then.

Revisiting the Street law project, 20 years into the history of the new South Africa, has caused me to reflect deeply on the changed society we now live in. In particular, the 15 drawings relating to gender and sexual violence have occasioned a profound engagement with the nature of South African society today and the relationship between sexual violence and the emotional infrastructure of our lives, especially the impact of accumulated hurts, repressed desires, unfulfilled aspirations and shattered dreams.

Over the last few weeks of working on this project, as I have grappled with the challenge of depicting violence against women and children in cartoon form, I have also become hyper-aware of the extent to which gender-based violence is manifested all around us on a daily basis. The headline-grabbing Oscar trial and ongoing press reports of child rape cases, combined with the less visible instances of gender-based oppression and humiliation that, once sensitized, one encounters at every turn, have been constantly with me as I have been drawing, at times infusing my soul with a feeling of great sadness. I hope the resulting drawings succeed in demonstrating the capacity of comic art to engage not only with light, humorous themes, but with sorrow and anguish as well.

The act of stitching this set of drawings together with red embroidery thread calls to mind quilts that have been made to draw awareness to HIV/AIDS and other gender-related issues. The act of hand-stitching, traditionally a womanly activity, has strong communal and contemplative associations. I hope that this “quilted” set of cartoons will, in the process of being stitched together, become a gestalt that engages the viewer in a rumination on the relationship between gender and violence, and the extent to which these forces inhabit our lives. Furthermore, I hope that the “cartoon quilt” will function as an integrated narrative artwork that will impact on the viewer on a number of levels – intellectual, emotional and visceral.

Angela Buckland

‘Grand’mothers of Shayamoya

The word grandmother has taken the meaning of ‘grand’ to extraordinary unexpected levels for many elderly women living in South Africa due to HIV/AIDS. Most grandmothers have had little time to grieve the loss of their own children before they take on the new responsibility of caring for their grandchildren. Grandmothers are at the stage in their lives when they should be cared for. Today many grandmothers absorb the weight of the broken family unit, making their role vital to the future survival of their communities.

doung anwar jahangeer/dala

the pavement is an example of a self transformed space, a truly public space.

its singular function of a walking space of the past has been rightfully appropriated and layered with a multitude of other functions after the fall of apartheid. a few of the new functions include restaurants, hair salons, traders, healing spaces etc. And at night the pavement turns into a home for many homeless. the pavement also in a lot of ways encompasses in a visual form the subversion of the rigid grid of the city by this organic force. the main structure through which this spirit is captured is the traders’ tent/gazebo. omnipresent in the city but yet transient in its form and essence, the tent/gazebo challenges the core of institutions fixed in their frightened form. this is an architecture without walls. philosophically this provides an appropriate vision for a necessary deconstructive intervention while engaging with the entropic urban phenomenon.

the uplifting possibility to dismantle the utopian foundation cannot be concretised without insightful self-reflection and the design practice in general. we need to abandon our ability to usefully unearth knowledge of the future through design and speculation. we need to recover material for a productive design practice from the dystopian, from our waste landscapes, our technological errors and dehumanising nature. we need to engage in experiments that provide a lens on the future and a critique of the present and in so doing collapses future and present into the same time-frame excavating tomorrow’s thoughts today. on a more practical level the traders encounter daily difficulties of storage, proper infrastructures, ablution facilities etc. there is a need for an infrastructure that also recognizes the social as a part of the whole of urban development. this is where “stepping into freedom” aims to tap in the ingenuity and solutions of everyday people to celebrate, value, acknowledge and welcome the potential in creative practices as a unique proponent in facilitating this humanization process.

One need only observe the pavement, where all cultural/political/economic/social life is played out, to recognize the power and potential of the in-between.

Bakhuli Emmanuel Many

Cato Manor, the area localized in the valley of the University of Kwazulu-Natal’s Howard College, it is a place over-flowing with history and with people. Here, African and Indian city dwellers founds a place to live through the first half of the twentieth as the city took shape around it, drawing from the cheap labour its inhabitants provided.

My photography works took place there at 2013 which my focus was on interior of places where people lives just to see about what we calls poverty or what’s poverty, and also what we call organization, by seeing the interiors of the place where people of Cato Manor lives.

The different façades of actual Cato Manor by these aspect of inside makes me to conclude by say this, sometime we human being we thinks poverty it’s only about money but I’ll say poverty can also be about interior of our mind or also spiritually.

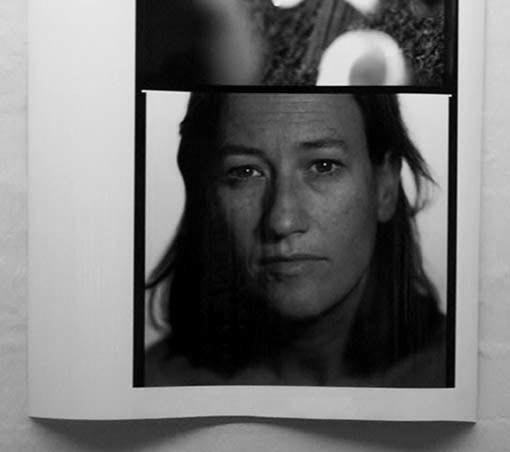

Grace Kotze in collaboration with Vulindlela Nyoni

One of the aspects that pull me to create is my reverence for humanity and the world in which I live. This path led me to befriend Vulindlela Nyoni, the subject of these works. After meeting him once and being an avid admire of his work, I knew that I wanted this person in my life. So I went ahead and invited him to dinner which developed into a valuable friendship. His sense of ethics in person and art making, were ones that held me and facilitated our friendship. He has been a subject in my paintings on numerous occasions as his person allows me the chance to explore my own issues without being flooded by the tone of his being.

Out of our friendship and mutual respect grew this project, one were we would explore our individual and shared concerns for the idea of the artists muse. We each worked with the physical image of the other while exploring both shared and personal ideas.

I am constantly fed by my “muse” which becomes a means of self-discovery working as a facilitator to my personal questions I may have at the time. The muse is a platform for visual verbalisations where upon hearing my voice, clarity is often reached. So often the questions are not understood but the process of paint and examination of the subject leads to clarity of mind. If the art making process is approached with authentically, as with a friendship, an understanding of a direction where discoveries will develop is highlighted. Thus leading me in a search for a muse whose person holds aspects of my being that in the looking at their physical and emotional beings may lead to my growth.

Often echoed alongside my use of the human muse is another subject that expands on my given concerns, with are explored concurrently. In this respect it is that of clouds. In order to explore humanities internal world in a state of highly person introspection I found that the best subject for such reflection was that of an amorphous subject. On trying hard edged manufactured and natural objects they jarred with the distanced state one requires when visiting ones highly private self. An area I was exploring at the time. So I eventually settled on the subject of clouds which hold a disconnect from ones surrounds and dreamlike state. Such a state was one I was very familiar with at the time of creating these works, where I isolated myself from others, visiting a highly private self where I paid attention to regain an internal understanding in order to heal.

Jeremy Wafer

Paradise was the title of a recent exhibition of the artist’s work in Johannesburg and is the name of an abandoned railway siding in the remote Northern Cape region of South Africa. The site which bears the traces and evidence of its former use, provoked a number of works in sculpture, video, drawing and photography reflecting on themes of possession and dispossession, of removal and loss, and the ways in which these concerns are played out on the intimate scale of personal experience and feeling as much as on the larger stage of the political. “Level” 2013 and “Yellow House” 2013 extend this series into more specific references to conditions of locatedness and dislocation.

Karen Bradtke

“The Morning Series” came about as I woke each morning and observed the morning light penetrating the curtain in my bedroom. With my cellphone next to my bed, used as an alarm, I started photographing the light coming through. These images were taken over a period of a few years.

What places these images into a South African context, a place where I live now, is the presence of the burglar bars in the images. It affects me. It reminds me of how we need to live with bars on the windows and makes me feel sad about this fact. It is also a reminder of how our society has become so violent.

I look back at my childhood, as I do in many of my works, and think about how I grew up where we did not even lock our front door! Now I find myself getting older and getting angrier about the politicians not doing anything about the escalating crime, but also, we as a people, seem to be just accepting it. The South African Bill of Rights says in part:

12. Freedom and security of the person.

Everyone has the right to freedom and security of the person, which includes the right-

a. Not to be deprived of freedom arbitrarily or without just cause;

b. Not to be detained without trial;

c. To be free from all forms of violence from either public or private sources;

d. Not to be tortured in any way; and

e. not to be treated or punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way.

In creating my work and the method I use to present the work, there is a physical aspect to it where I rub the image to make it ‘cleaner’. Each image presented is a one-off in that the manipulation of the image will not allow the image to be the same each time. It is originally a photograph taken with a cellphone then transferred onto fabric. The transferring of the image gives it a more ephemeral quality reflecting the drowsiness upon waking. The fabric used for this body of work is a similar curtain to the one in the images, then cut-up and rehung as ‘curtains’.

Mbongeni Buthelezi

My work is predominantly recycled plastics on plastic, melted with a hot air gun. I am interested in figurative and non-figurative subjects. My figurative subject matter is the physical condition of township life and how this affects the way of life, which is one of survival. These experiences are sometimes interpreted in a non-figurative style depicted in organic forms and shapes like arms, hands and torso, etc., as well as landscapes. I believe both styles in my work better describe life around me and my environment.

I collect rubbish and create something beautiful from it. I collect something that has no value and give it new life. That’s what we can do with ourselves and our lives.

Nanda Soobben

A book of my cartoons is being published to commemorate the 20th Anniversary of our Democracy and I use some of the cartoons from the book to show different aspects of our history over the past 20 years.

Pascale Chandler

The work invokes issues of censorship as well as the function of creativity within the structures of the social space. It also has defined the divide between and within the political process as it embodies itself as a collision of power and multiple egos traded as particular perspectives on social identity, which need to prevail.

The painting explores this metaphorical sombre space where a sinister machine secretly shifts a mass of debris. The carcass of the Three Elephants shapes and defines a particular vision and moment of our history as a collision of values. This Andries Botha sculpture disintegrates and rearticulates as a fragment of collective social conscience in decline now expressed as a “fragment” of Durban history. The Human Elephant Foundation is a creative metaphor which defines the conceptual space of the actual work, that which interprets the collective space within which we live as opportunity for imaginative transformation. For two years the work has been held hostage by The eThekwini Municipality.

Paulo Menezes

This photographic body of work was made in the city of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, during the year 2013.

Susan Sontag writes in her essay In Plato’s Cave; “Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality […]”. Standing on the streets of the city, I realise that these walls have become an ever-present face, gazing static onto an ever-changing and fluid landscape. In an attempt to decode the latent images that brush on and off of these walls, I present these miniatures of reality. Light and shade, concrete and sky, entering and exiting.

This work visualises an internal exploration into time past and time that is still to come.

Peter McKenzie

Cato Manor, a space confounded by its existence, tenuously reaching for its space in the democratic sun, expectations tempered by debilitating realities, potential abounds in tandem with transformation’s gains, the fabric of life interwoven into a tableau of possibility, the picture not yet clear.

The photograph and memory or as memory, the image merely presenting the possibility of narratives, the context in tension with the content, meaning derived from the coalescing of then and now, the image shadowed by community narratives, communities defined not chosen.

Amajondol: houses or homes? Emakhaya (or) elokishini. enigma, the confluence of democracy’s intent, not result. The quiet visual approach counterpoint to the images of angry service delivery protestors. The camera not freezing but embodying, the structures bearing the burden of societal truth, the confluence of democracy’s intent, not result.

Robert Domijan

‘When there is chaos, who will listen to whom’

Drawing a parallel between the ‘1913’ strikes and ‘Marikana’ a century later, it is safe to say the legacy of apartheid continues to undermine the development of a stable society in South Africa, with most parties participating in the difficulties faced by an emergence of an even more complex spectrum of political beliefs, fair distribution of land sharing, (which continues to be an emotive subject), BEE, cultural needs, etc.

I produced a small cast of characters in the painting ‘SHOUT’ – it is not about apartheid, for there are certainly not enough sufficient tools to produce a representation of such a vast and complex issue spanning over this century and more.

The notion is that in this scenario, the political landscape has not changed, as in ‘the more things change, the more things remain the same’. This historical oppression of the people is re-enforced by the savage exploitation of the countries natural resources and to this day, this continues. It has been plundered, raped and ravaged and this motif has been depicted herein.

The suited ‘colonial’ mans self absorption is typical of himself, cut of from the nature of this land. They, the ‘colonials’, (the old and the new) seem totally divorced of this landscape around them, and the reality of the millions around them, whose pleads they ignore.

I intended to capture some sort of truth behind this seemingly natural landscape and so too have this small cast of characters, who for a century and more have been ‘shouting’, but still have not been heard!

Sifiso Ka-Mkame

Ka-Mkame’s work is very decorative, demonstrating nostalgia for African symbols; a quest that became more urgent and challenging for him after SA’s first democratic elections in 1994. With a group of like-minded artists in Durban, he began searching for symbols of an African identity beyond the confines of his own region and this is reflected in his paintings. He works on a number of paintings simultaneously, building up dense layers of colour with oil pastels and scratching patterns into his images. He usually titles his work and this provides the viewer with the beginning of the story or narrative that has inspired his work.

Themba Shibase

My current experiments in drawing are meant to address the following:

• Rediscover my appreciation for drawing as a very immediate medium for transferring ideas into practical visual form/images.

• To explore the identity question (which has been my interest for a very long time) beyond the confines of race politics, but to stretch it such that it encompasses class, gender and sexuality , – the latter being something we all live with everyday of our lives yet still treat as a taboo.

• To generate and refine ideas or images which will be explored in various other media.

The paintings included in this show are examples of my engagement with the intersectionality of race, gender, class, and politics. South Africa over the last two decades has undergone so much transformation in these areas that the journey can best be described as a roller- coaster ride, except in some cases human beings paid the high price of suffering or death as a result of ignorance, intolerance and hatred. Gendered violent crime (Pistorius/Steenkamp), class related violent crime (State/Marikana miners), etc are but a few examples which characterize the extreme and sad part of our 20 years into democracy. Greed and corruption form part of the list and the diptych ‘The Catastrophic Encounter between Modernity and Africa’ 2014 is inspired by my observation of such matters in contemporary South Africa.

Umcebo Design

Umcebo Design was born experimentally with Robin Opperman in the 1990’s while he was working as an Art Teacher at Ningizimu School for the Severely Mentally Handicapped. The idea of roping in community support for art and craft projects in all shapes and forms with a view to generating income and gaining exposure for the art programme became the seed idea for what was to become “Umcebo Trust”. While the Trust achieved much success and a lot of attention and publicity, it was ultimately closed down due to lack of funding and overhead pressures. Robin, however, transformed Umcebo Trust into Umcebo Design. The art and craft concept remained the same, but the modus operandi become more business-like and lean. Robin now operates with a small core group of artists / crafters / consultants who bring their unique skills to the party. Where possible, work is outsourced to local community crafters who are able to make good money for themselves on a commission basis. Umcebo Design continues to produce unique art and craft pieces and works closely with other craft-centred organisations in the Durban area.

Vaughn Sadie

Sadie’s production over the last few years within public art and public practice, have integrated not only projects that would be considered personal projects, but has also extended toward a position as a critical consultant and researcher within larger and more inclusive projects. This work has been broadly concerned with public arts, its articulation within discourse and its development towards a more responsible and responsive cultural production. His work within 2010 ‘Reasons to Live in a Small Town with the Dundee: Living Within History’ project, stressed research, participatory practice and collaboration.

The maps presented here, represent Sadie’s continued engagement in strategic, research- based mappings of complex and specific contexts and illustrate a greater understanding of the social, geographical, urban and built environment that informs and shapes Cosmo City and the Revolution Room project.

Further to this it represents Cosmo City’s relationships to neighboring communities and its immediate history, a way forward to properly investigate the contemporary reality of such housing developments and its links to broader narratives nationally, politically and socially. These in turn provide a visual language and a base from which this public art project can build on and be informed by. As a practice, this instance of map-making reveals Sadie’s concern and interest in the importance of research and investigation into the methodological development of a true participatory public practice.

About Revolution Room:

The Revolution Room project – a collaboration between Picha (Lubumbashi, DRC) and VANSA – seeks to explore new ways in which museums as public institutions can project themselves more forcefully into the public realm, through interventions in ‘common space’ developed out of complex collaborations between artists, citizens and museum professionals. The project will involve museum professionals working with artists and local partners/collaborators in developing projects in Cosmo City, a post-apartheid urban settlement in the north-west of Johannesburg.

The project also seeks to forge institutional linkages, collaborations, and a community of practice between South African, broader African and European institutions and organisations, borne out of the practical experience of developing a shared project.

The project builds on VANSA’s work in the area of public practice over the last few years through projects such as Two Thousand and Ten Reasons to Live in a Small Town, and our involvement and consultation with various public and private sector organisations.

Wesley van Eeden

My artwork takes a critical look at social, political and cultural issues that I experience while living in South Africa. For “Secret Country” and “The Pigeon Keeper” I explore using digital technology to create a contemporary look and feel of the subject matter that I create. While ” The Lying Lion” explores a more traditional approach with acrylics and paint brush. All of these works explore a visual narrative about the struggles of living in South Africa. “Secret Country” explores the idea of a place that has not been found or been disclosed by the lack of education and opportunities that a government should be providing its people. “The Pigeon Keeper” uses the scales of justice that has been replaced by starving pigeons and food that has been wasted which is a metaphor for a people that are dependent on hand outs from a government that is inefficient. “The lying lion” again explores a corrupt system that is un phased by its people, relaxed and broken arrows sit by the wayside, it continues to lie down and spread lies to its people.

Woza Moya Crafters

Thank You Democracy!

When making an artwork with a group of over 100 people, Woza Moya always has the challenge of how to give everyone a voice and how to allow them to lend their own identity to the work. Our forte is usually enormous beaded patchworks, but this time we wanted to make something that would take us out of our comfort zone. We decided to approach the work in a very simple way and worked with the concept of Cameos. Cameos originate in ancient Egypt and Greece and were used to pay homage to great leaders or Deities. Cameos became very popular in the Victorian times and were a symbol of prosperity and signified wealth; Our way of commemorating democracy is with the people of Woza Moya sharing their experience of living in our new Democracy – here the Cameos signify the prosperity that democracy has brought, whilst also celebrating each individual. Although Cameos are just an outline, they at once have great intimacy and have some mystery to them – everyone loved seeing what they looked like from the side!

Process

A photograph of every crafter was taken, turned into a silhouette and a short interview was conducted about what our Democracy meant to them. Most comments were very positive about how many things had improved since democracy: improvements in education, housing , basic services and improved living conditions featured strongly in the comments. Equality, improved interracial communication (which made many of the crafters happy) and the ability to vote were also mentioned. For many of the people interviewed the idea that democracy equals freedom came out strongly – the freedom to associate, freedom of speech, freedom to be yourself, the freedom of movement (a few of the older crafters mentioned how relieved they were that they did not have to carry a pass anymore). One of the crafters said that freedom is for everyone, so it seems from the interviews that freedom in South Africa makes people happy and promotes unity. Some crafters cried whilst being interviewed and were able to release emotions that they had not been able to express to anyone in a long time; it was a very emotional process for everyone involved, which we were not really expecting. Even reading all the quotes before writing this made me cry, so thank you Democracy!

After the interview process every person was given their silhouette to bead and this was sewn together in our interpretation of a democracy flag. The work is an uncut version of what Democracy means to the people – read it and weep.