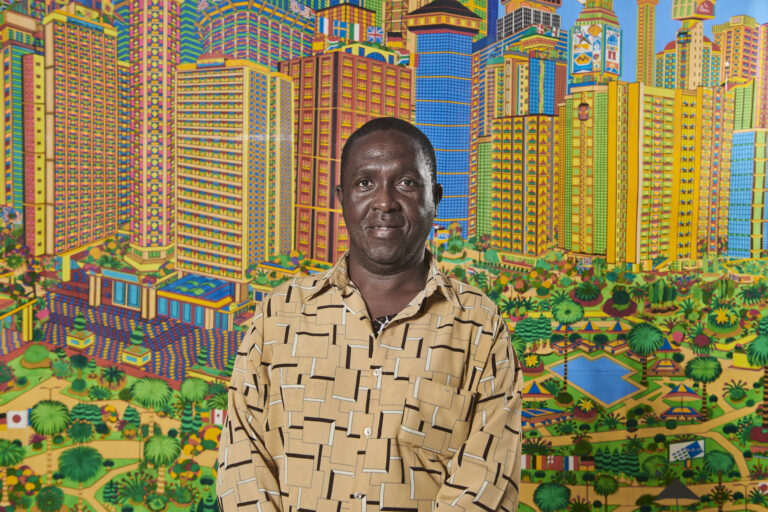

Paradise? Derrick Nxumalo

Date

Artists

Derrick Nxumalo

For more Info, contact us on: gallery@kznsagallery.co.za

Paradise?

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun

Or fester like a sore-

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over-

Like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

ー Langston Hughes, Harlem, A Dream Deferred (1951)

What happens when dreams of freedom, equality and social justice are suspended and at risk of never coming true? In A Dream Deferred, the Harlem Renaissance poet, Langston Hughes compels us to consider the hopes and aspirations that people hold on to when dreaming (willing…) another world into existence. What are the consequences for the idea of the nation and its people when these aspirations are not met? In positioning the idea of Paradise? as paradoxical, this exhibition considers how notions of hope and hopelessness; utopia and dystopia; and of futurity and unresolved pasts can exist simultaneously and are tied to the dreams we have for a place.

Fuelled by myths of the ‘exotic Africa’, Durban, in the colonial settler imagination, was seen as a tropical paradise. The projection of Durban as paradise constructs the city into a landscape of fantasy, consumption and leisure, all of which continue to delineate the city in the contemporary social imaginary. In a critical reading of the city’s colonial past and the failings of the current political regime, Paradise? juxtaposes tropes of Durban as a city of leisure against the city’s social realities of poverty, inequality, and spatial apartheid. The uneven distribution of who can participate in and consume leisure is addressed deftly throughout the exhibition.

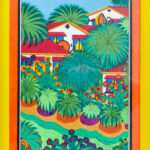

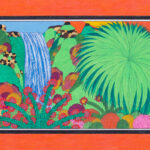

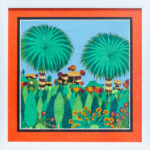

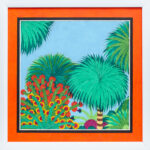

The bricolage of inner-city architectural details and motifs, imagined buildings, and the play on scale and geometry, renders the Durban cityscape strange or alien. The city becomes a transnational utopia where ideas of statehood are revisited through a reprise of national flags and high street-style branding. The viewer or onlooker is invited to participate in the making of these alternate city-worlds, but only from the vantage point of alterity. From this perspective, the viewer must confront their own version of paradise, while negotiating the ideological implications this brings. The use of colour in these city-worlds is reminiscent of the South African flag, referring to the ‘rainbow nation’ idea of national consciousness that was debunked soon after its conception. In addition to the cityscapes, the suburban garden is a recurring theme here, invoking critiques on suburbia and its associated privileges, excesses, and banality. In the landscape and garden scenes, the artist engineers taxonomies of novel botanic forms that animate these sites, again framing that which appears familiar, as alien.

Returning to Hughes’ question, what happens to dreams that don’t manifest? we are left with further questions: what lies beneath the veneer of the perceived Paradise? is it possible for deferred dreams to be resurrected? or, must they explode in order to make way for a radically different world?

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2020

43 x 33 cm

R4500

Acrylic on paper

2021

32 x 19.7 cm

R1 200

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2021

55.4 x 45.4 cm

R5 500

Acrylic on paper

2021

86 x 26 cm

R4 500

Acrylic on paper

2021

100 x 70 cm

R11 500

Acrylic on paper

2021

85.7 x 70 cm

R11 500

Acrylic on paper

2021

60 x 30 cm

R4 000

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2020

38 x 38 cm

R4 500

Acrylic on paper

2020

64,3 x 18,6 cm

R3000

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2020

38 x 38 cm

R4 500

Acrylic on paper

2021

32 x 19.7 cm R1 200

Acrylic on paper

2021

32 x 19.7 cm

R1 200

Acrylic on paper

2021

30 x 20 cm

R1 200

Acrylic on paper

2017

32 x 19.7 cm

R1 200

Acrylic on paper

2021

32 x 19.7 cm

R1 200

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2020

38 x 38 cm

R4 500

2004 – 2019

Acrylic and pen on cotton needle point paper

800 x 375 cm

R1 460 000

Acrylic on paper

2020

100 x 70 cm

R11500

Acrylic on paper

2021

86 x 26 cm

R4 500

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2021

137 x 61 cm

R15000

1998 -2021

Acrylic and pen on paper

1000 x 231 cm

R2 000 000

Acrylic on paper

1998 – work ongoing

1770 x 132 cm

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2021

45.4 x 35.4 cm

R4 500

Acrylic on paper (framed)

2021

45.4 x 35.4 cm

R4 500

Acrylic on paper

2021

32 x 19.7 cm

R1 200

Acrylic on paper

2021

100 x 70 cm

R11 500