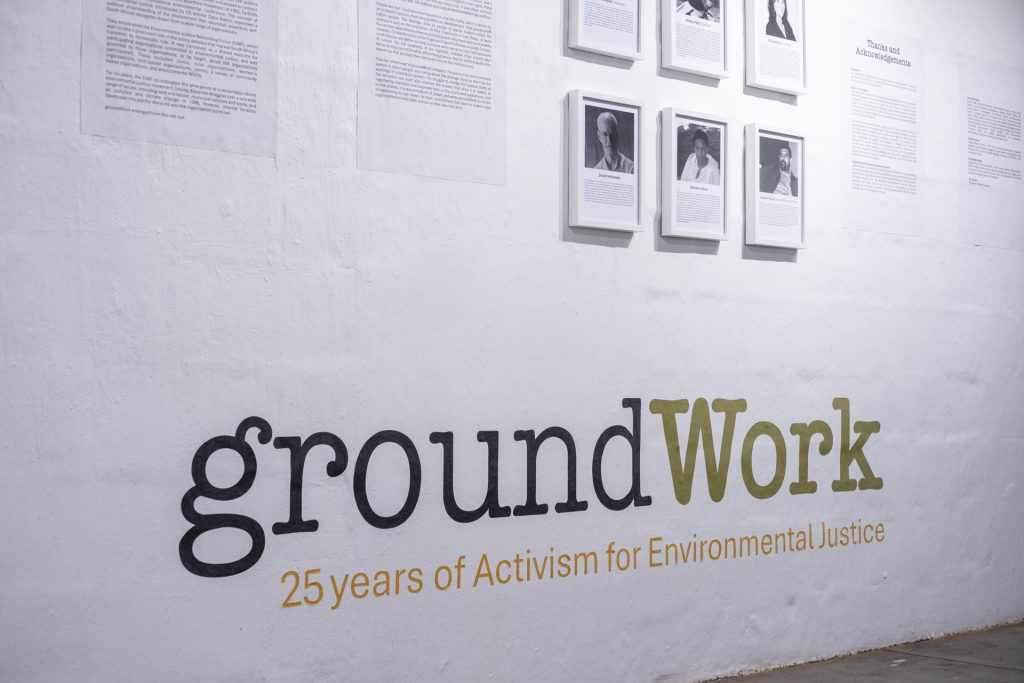

groundWork: 25 Years of Activism for Environmental Justice

Date

Artists

This exhibition is curated by Vaughn Sadie.

For more Info, contact us on: gallery@kznsagallery.co.za

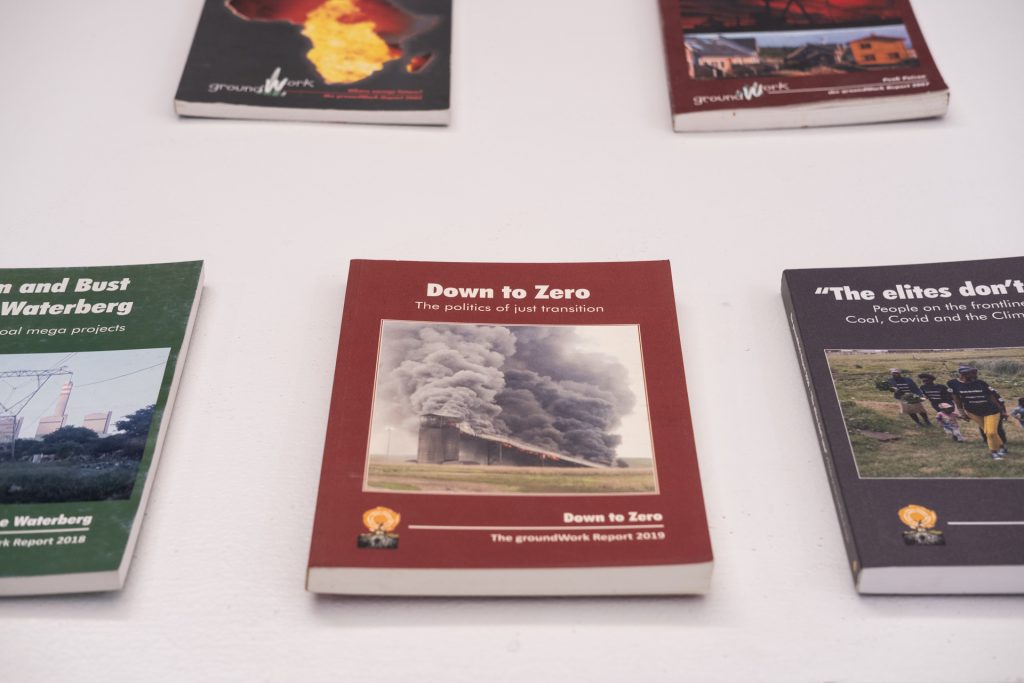

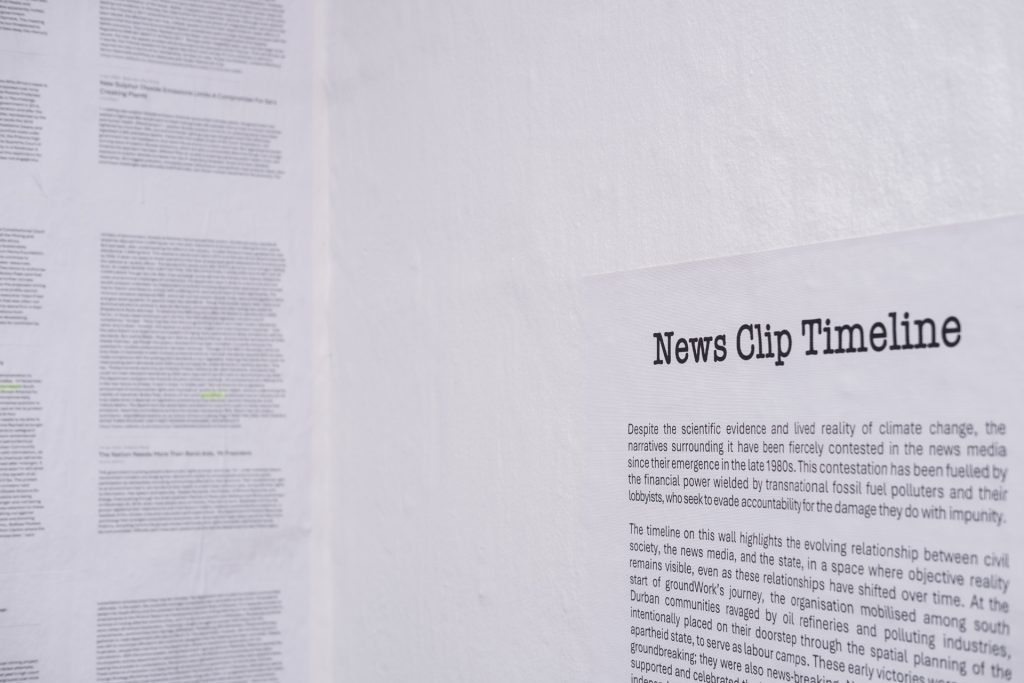

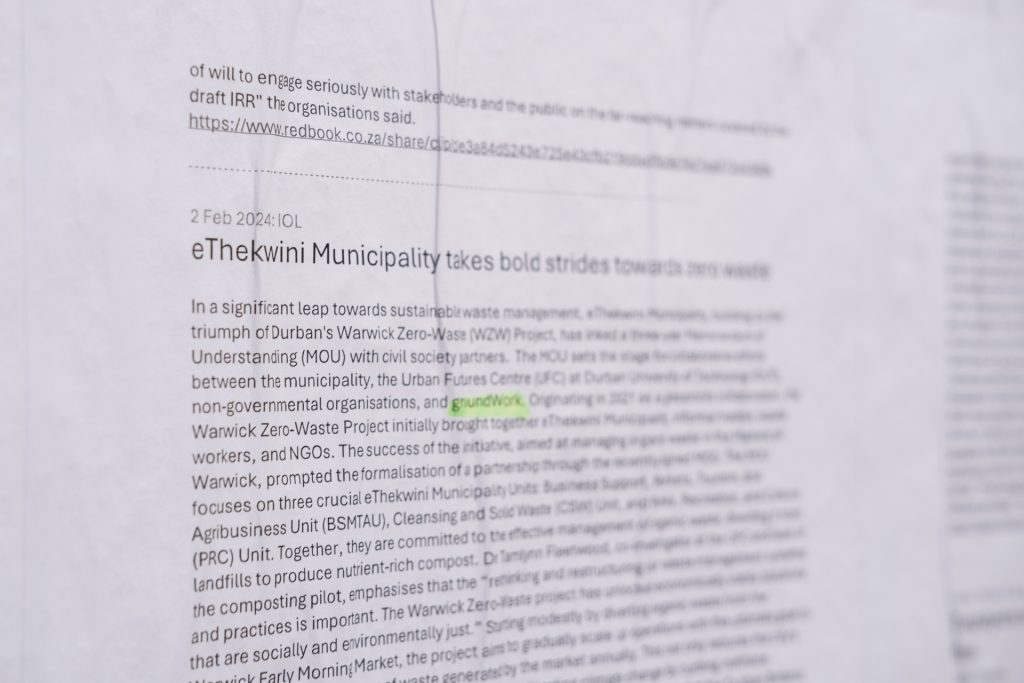

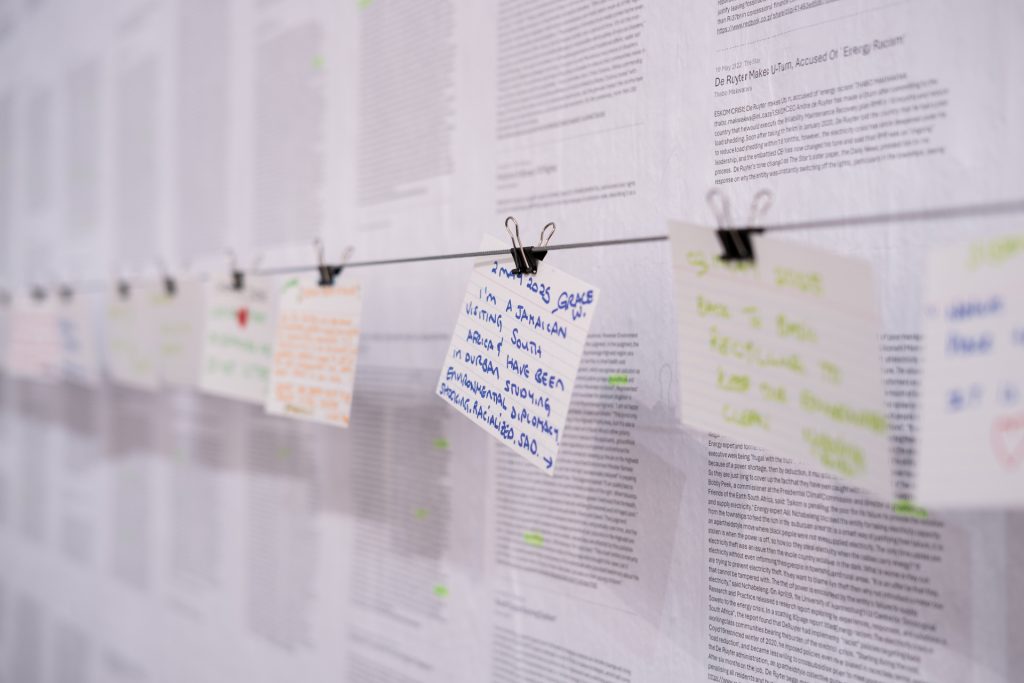

The exhibition, thoughtfully developed through a participatory approach in collaboration with the dedicated activists and professional workers from groundWork, offers a profound exploration of the organisation’s rich and impactful history alongside its partners over the past 25 years. This exhibition invites attendees to delve into a comprehensive and dynamic archive featuring a diverse array of documentary photography, evocative posters, striking banners, informative publications, films and artefacts, which includes reports, affidavits and a range of correspondence. These elements vividly illustrate groundWork’s pivotal campaigns and highlight their substantial contributions to shaping South Africa’s socio-political landscape and pursuing environmental justice.

Curated by Vaughn Sadie, drawing from the extensive resources of groundWork’s archive, the exhibition is a powerful testament to community resilience, activism, and advocacy in the complex backdrop of post-Apartheid South Africa. Visitors will have the opportunity to experience compelling narratives and hear the authentic voices of those passionately engaged in environmental justice, shedding light on the struggles and triumphs that have defined this journey.

Lead Image Caption: Engen Oil Refinery is South Africa’s oldest oil refinery, commissioned in 1954. It ceased operations as an oil refinery in December 2020 after an explosion at the ageing facility damaged both the plant and the surrounding neighbourhoods of south Durban.

A critical Review: Groundwork 25 Years of Activism for Environmental Justice

By Snesizwe Mahlalela

“May we never have to compromise our fight for a true and just world, for that is the compromise that Madiba would not want us to make.”

Sven “Bobby” Peek – Activist, Co-Founder of groundWork

The KZNSA Gallery, presents the exhibition groundWork 25 Years of Activism for Environmental Justice. It is an archival project created in collaboration with the dedicated activists and professional workers from groundWork and is curated by Vaughn Sadie of LIGHT PLACE. The exhibition presents material (documentary photographs, protest banners, educational publications, and personal artifacts) that chronicle the struggles and triumphs of environmental activism in South Africa bringing together over two decades of struggle! Unflinching! Uncompromising! Sadie embedded themselves in the organization for months before the installation process began. He sat through over 40 hours of meetings, not as a distant designer, but as an active listener. The result is an exhibition shaped by groundWork itself – participatory, fragmented, and a deep intentional reflection of these years, almost meditating on how far they have come while still gesturing toward how far we as society still need to go.

This is not simply a celebration. It is a reckoning!

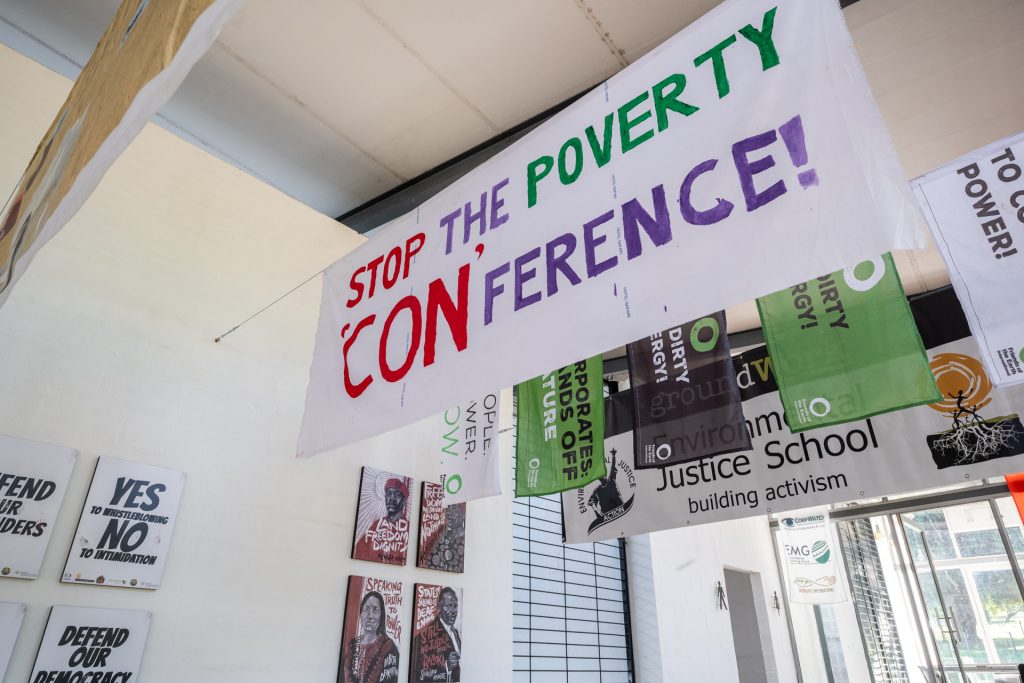

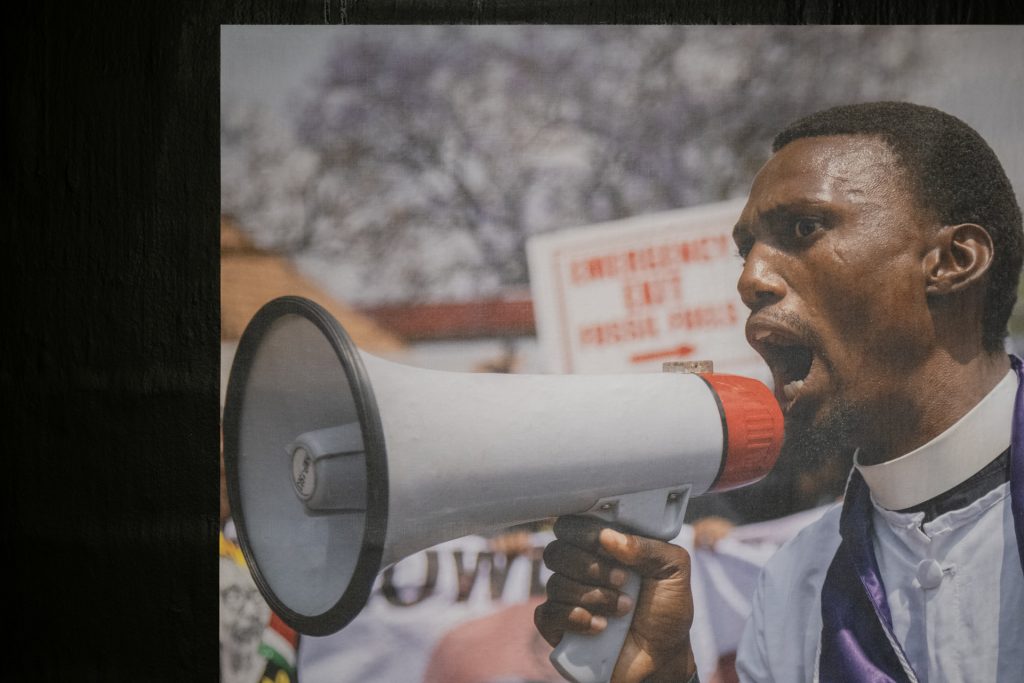

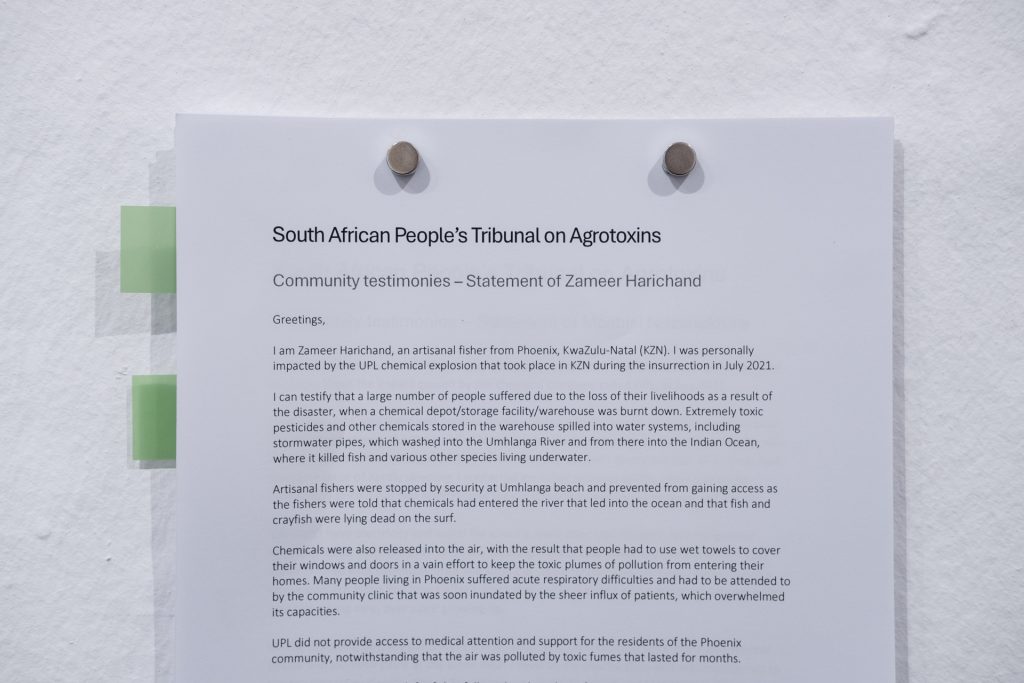

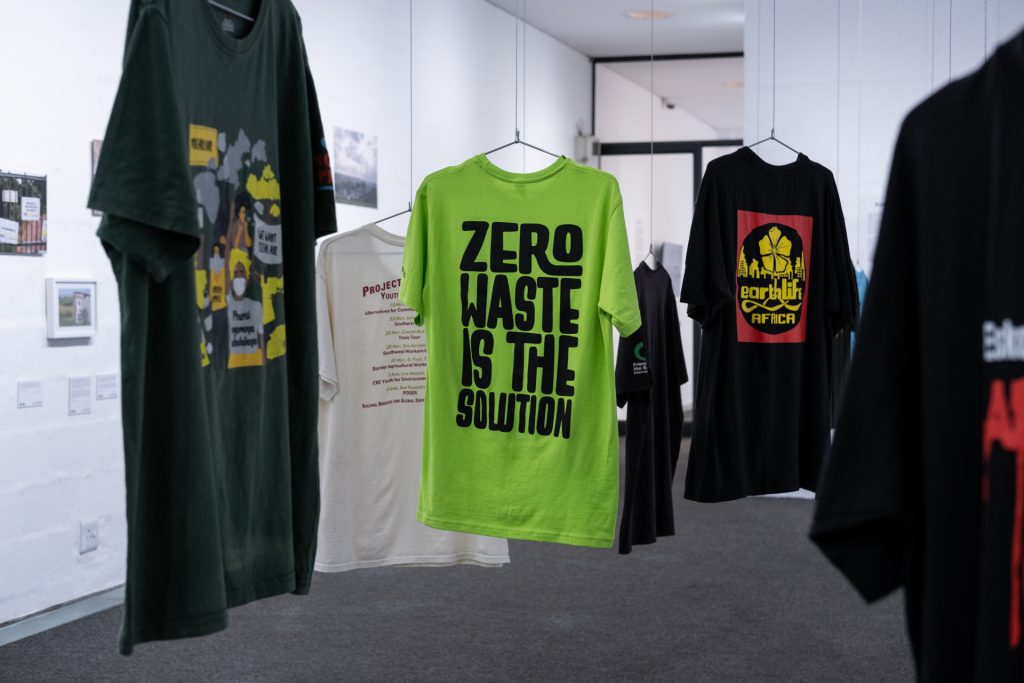

When you walk into the café which is the entry point of the KZNSA gallery as well as the starting point of the exhibition, you do not step into a typical gallery setting. Instead of clean white walls and quiet order, you are greeted by large banners hanging across the space, stretching into the corners and overhead beams. These banners immediately break free from the usual frame of how exhibitions are supposed to look! This reminds me of Meschac Gaba’s Museum of Contemporary African Art at the Tate Modern (2013), where he used every day lived-in spaces like a café to challenge museum traditions built on colonial imaginings. The materials on display at the café, posters, pamphlets, and placards, feel active – as if they could be picked up and used again at any moment. One article sign reads: “We are not collateral damage.” The message is clear and direct, speaking to the pain and resistance after the UPL disaster that we will later be educated about in the exhibition in the galleries Mezzanine. It is also in the Mezzanine where old protest T-shirts hang from the railing like flags, each one a memory from a different moment of struggle. This exhibition isn’t polished or removed from real life stuck to the “white cube” “4 white walls” doctrine. It is raw, alive, and present. It invites you to step in, not just to look, but to feel what is at stake. “This is a sliver of a deeper history,” says co-founder Bobby Peek. “We realized long ago that justice isn’t something you get by writing policy alone. It is something people on the fence line fight for every day and that is who this archive honors.”

groundWork’s commitment over 25 years is a timeline of wins and losses. It is a record of sustained attention of showing up, often quietly, to communities pushed to the edge of South Africa’s petrochemical and industrial zones. In the gallery, this long memory takes shape. You begin to notice how the space holds itself grouped loosely around campaigns that stretch across regions and years. The layout doesn’t shout; it invites you to look again. This is environmental justice that does not isolate the environment from the social. It binds land, breath, water, and body into the same frame. The exhibition asks: Who bears the cost of development? Who is rendered disposable? And who has kept resisting, even when the cameras turn away?

The exhibition is doing something subtle but radical. It refuses spectacle. Instead, it makes room for witness. That’s an important distinction. There is no single hero narrative here. The images and texts fragment, overlap, and return. They invite us into a slow, layered reading, what scholar Christina Sharpe, in her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, calls “wake work.” Wake work is the act of staying with the ongoing grief, trauma, and struggle that stem from histories of violence, not to resolve them, but to tend to them, to acknowledge how they persist in shaping the present. Vaughn Sadie, curator and artist behind the exhibition, describes the process as one of “refusal and reduction.” “My goal was to invite people into the complexity without overwhelming them,” he says. “groundWork’s archive isn’t neat – because the work isn’t neat. It’s protest, negotiation, grief, solidarity, lawsuits, song.”

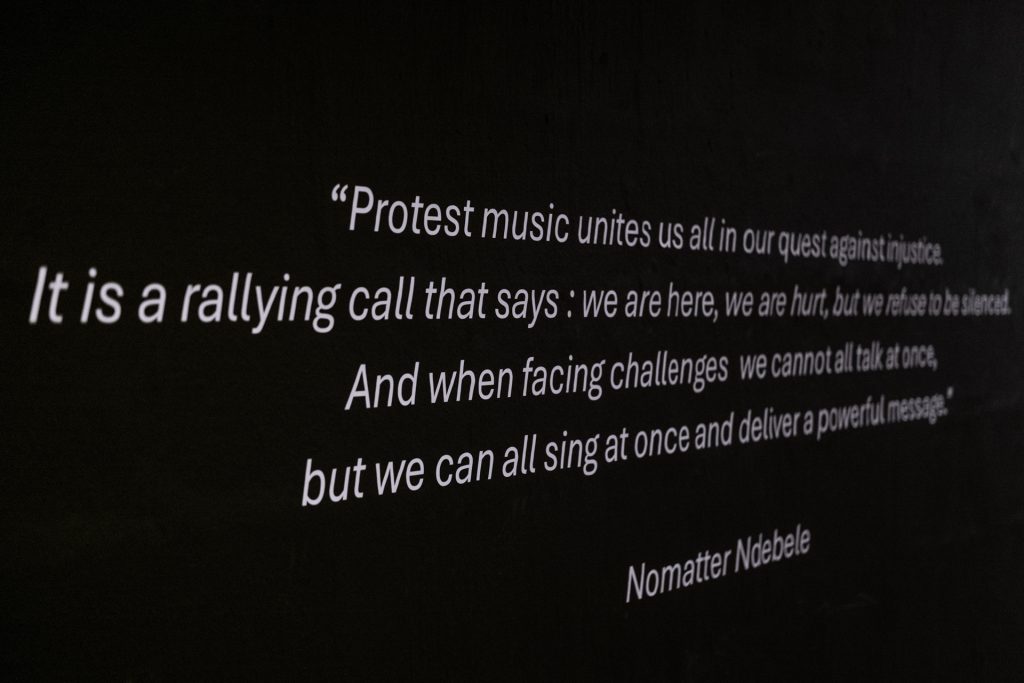

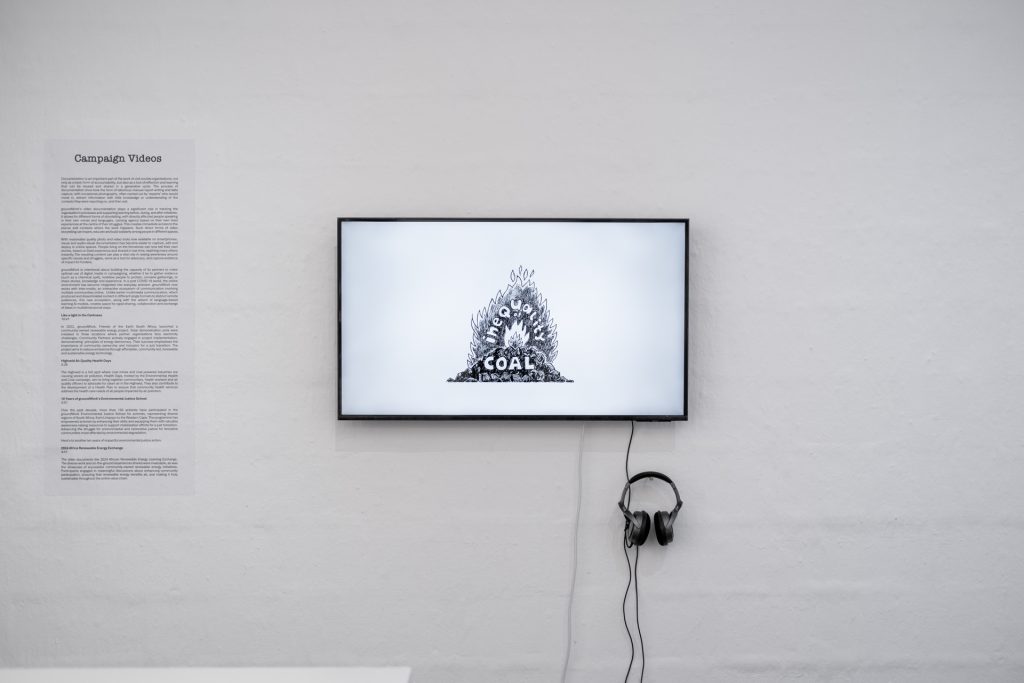

Tucked toward the back of the gallery, the Media Room may appear quiet at first glance, but it is layered and loaded. Here, the archive shifts registers using sound from past protest and visual storytelling to compliment the reports, publications, court documents, and media clippings displayed in the other rooms. It becomes clear that groundWork’s fight has been deeply strategic, waged through protest action, data, litigation, communication, and narrative control. For both Peek and Senior Campaign Communicator Dorothy Brislin, one space in the exhibition that stands out is this exact room. “It is deeply emotional,” says Brislin. “Even if you don’t understand the language of the songs, you feel them in your body. These are struggle songs, adapted through time, connected to land, pain, and community.” What strikes me the most is how the exhibition foregrounds community knowledge. The archive is not just institutional, it is deeply local. It remembers the people who spoke up at fence line meetings. The ones who tracked health impacts in their communities; who noticed when the coughing started; when the water started to smell differently; when the children got sick; who built coalitions; who kept receipts. These voices are not footnotes, they are the centre!

In the current climate crisis, where justice is often discussed in abstract, global terms, “groundWork: 25 Years of Activism for Environmental Justice” insists that the fight is specific, situated, and historical. It reminds us that South Africa’s environmental future cannot be separated from its political past, nor from the structural violence still shaping the present spatial apartheid, extractive economies, and environmental racism. The 2022 KwaZulu-Natal floods, which claimed over 430 lives and displaced thousands, were officially attributed to climate change. However, many communities pointed to longstanding issues like inadequate infrastructure, poor urban planning, and lack of maintenance as exacerbating factors. This disconnect highlights how environmental disasters often stem from both global climate shifts and local governance failures. groundWork’s mission aligns with these concerns, emphasizing that true environmental justice addresses both the global and the local. Their work underscores the importance of holding polluters accountable and ensuring that marginalized communities are not left to bear the brunt of environmental degradation.

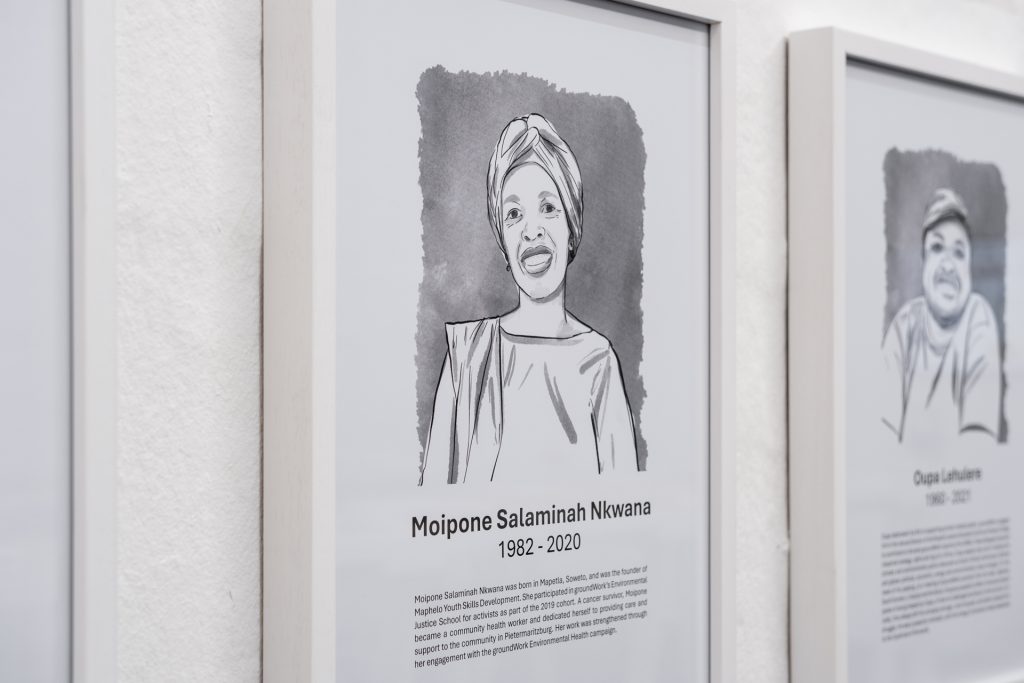

In the Park Gallery a memorial wall honours fallen martyr activists who lost their lives in the struggle for environmental justice. Their faces look back at us, reminding visitors that this work has come at a cost. It’s not only an archive of documents, but of lives risked and lost. A quiet message reads: “As you reflect on this wall, we thank those who gave their time and energy to this work.” It is a moment of pause and recognition. Across the exhibition, community is not simply a theme, it is the foundation. The people who gathered, who mourned, who organised and continued, are not placed on the edges of the story. They are the story

In its quiet insistence, the exhibition teaches us that the archive is not passive. It doesn’t sit still. It demands something from us. Reflection, yes, but also action. This is not simply a retrospective of victories or wounds. It’s a space charged with ongoing responsibility. As Bobby Peek puts it, “We are not just saying no. We are bringing solutions to the table. This is an activist exhibition. It is not static. It is about struggle, about care, about building.” The work continues, and the archive in all its layered textures calls us not just to witness, but to join.

Visitors are invited to engage with the stories of fence-line communities, those living closest to pollution and risk, yet furthest from power. While the exhibition documents past struggles, it also opened a space for ongoing conversation through lab talks, workshops, and screenings. But for those who cannot walk the gallery rooms or touch the banners, the invitation still stands: to listen more closely, to ask harder questions, to notice what is happening beyond the fence-line. Environmental justice is not just a campaign, it is a practice. One that begins wherever you are.

This article was written by Sneziwe Mahlalela. Mahlalela is intern at the KZNSA Gallery through the initiative funded by ArtBank. He studied at the Durban University of Technology, earning both a Diploma and an Advanced Diploma in Fine Arts. He is an artist, writer, and creative based in Durban. His work explores colonial and post-colonial histories, and the in-between spaces where culture, creativity, and cities overlap, especially in his hometown of Durban. He took part in Power Talks, where he shared a reading that reflected his passion for cultural conversations. He has also worked with KZNSA artresearchlab, contributing to collaborative, research-led projects that look at how art engages with urban life and social change. Through both his art and writing, Snesizwe stays curious about history, identity, and the ways creativity can transform everyday spaces.